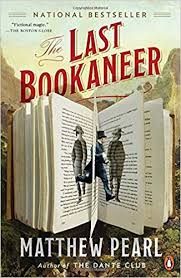

Honestly, it is never quite clear what the bookaneer does. Essentially, he (or, in one case, she) is a literary pirate, but the specific acts of the crime—unlike, say, kidnapping—remain somewhat mysterious. So, the narrative has a hole in it, the size of a molehill maybe but noticeable nonetheless. Still, there is so much to enjoy about The Last Bookaneer that anything resembling disbelief gets willingly suspended.

Back to the molehill, this lack of clarity about bookaneering. About a quarter of the way through the book, I was still struggling through the fog a bit. Much as bookaneer Pen Davenport was mystifying his assistant Fergins, so was Matthew Pearl, the author, mystifying me. Then again, I told myself, it is a mystery and therefore some mystification, expected.

Still, it is a relief when, about halfway through, some illumination pierces the fog, in the form of two examples, one following the other. The first example of a bookaneer, according to Fergins, came long before international copyright law, in 1887. He tells us this:

In 1514, Pope Leo X…granted exclusive papal permission to a printer named Beroaldo to reproduce the works of Tacitus. … [Simultaneously], one Alessandro Manuziano began printing the same book of Tacitus before Beroaldo was finished—…probably having bribed one of Beroaldo’s employees for the material. (198)

On the one hand is “exclusive papal permission” for a reprint, which surely amounted to a law in 1514. On the other is Manuziano’s surreptitious reprinting, which is clearly breaking that law. Meantime, Manuziano is committing property theft, probably via bribery. So, the fog starts dispersing. In the second example of bookaneering, it has turned out that Mary Shelley’s short story that evolved into her novel Frankenstein still exists. A bookaneer is hired by a shadowy collector to retrieve it; she does, whereupon she receives an “enormous payment.” (219) Again, there is theft of a literary work, and there’s this suspiciously “enormous payment.” The fog continues to disperse—but never entirely.

But enough of the minus. Much about The Last Bookaneer is absorbing, to start, the novelty of the story framing the story of the bookaneer. At first, the frame story in The Last Bookaneer lacks drama. On the train where he works, a waiter meets a bookseller, who, eventually, tells the story of the last bookaneer. The unexpected bond between the two and the waiter’s utter absorption in the story cast a spell besides the thrill of the story itself.

As with Matthew Pearl’s portrait of Longfellow in The Dante Club, it is his portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson that’s compelling, more so than the story of the bookaneer. When a servant eats a pig meant for Stevenson’s stepson’s birthday, Stevenson declares, “We have lost far more than food meant for Lloyd’s birthday. We have lost our trust in you, which used to be so great, our confidence in your loyalty.” (122) And he doesn’t stop there. Stevenson conveys a weighty authority that, despite his wasting sickness, he never loses. A memorable character.

Then there is the bizarre triangle of bookaneer Davenport (“Mr. Porter”), Davenport’s assistant Fergins, and bookaneer Belial (a horrible pseudonym)—hardly romantic, but nonetheless intense. There is Fanny Stevenson’s mysterious warning to Fergins to leave the island. Most of all, there is the excitement of the race to procure Stevenson’s last novel—and also, surprisingly, the excitement of the aftermath. Here, the frame story provides a shocking plot twist.

A diamond in the rough from Matthew Pearl!

You must be logged in to post a comment.